Understanding Viterbo’s relationship with Native American boarding schools

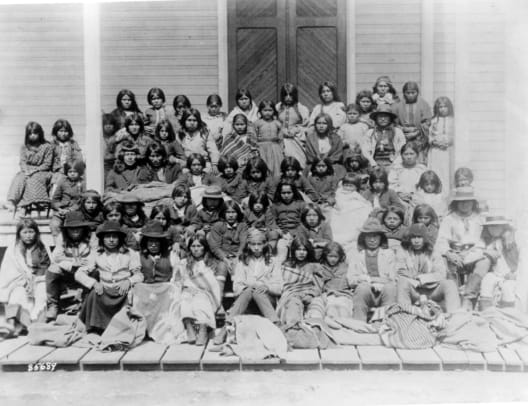

Native American children at boarding school

November 16, 2022

On Nov. 3, Sister Eileen McKenzie, former president of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, spoke at the “Theology on Tap” event hosted by Dr. Emily Dykman, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Viterbo University. Along with Henry Greengrass, Center Director of the Ho Chunk Nation, Sister McKenzie educated the community on the negative effects of Native American Boarding Schools and the ways in which indigenous cultures have been systematically assimilated in the United States.

A main goal of this presentation was to examine the difference between the intent and impact the Viterbo Sisters of Perpetual Adoration had on the St. Mary’s Boarding School in Odanah, Wis. The Sisters operated the school from 1883 to 1969. The intent of the school was to educate and assimilate Native Americans using ideas rooted in Western Christianity. To illustrate the unforeseen impact the schools had on Native populations, Sister McKenzie recalled a familiar quote: “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions.”

At one time, the school was a source of positivity for the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. Sister McKenzie said that it was a “Great experience for the Sisters. It gave them pride, energy and joy.” But this history does not consider the actuality of the situation for the Native Americans, which included limitations on religious freedoms, forced resettlement and relocation, and genocide. One statistic that was cited repeatedly during the event best illustrates this different between impact and intent: only one percent of indigenous populations survive America’s history of colonialism.

Henry Greengrass helped Sister Eileen learn the hidden history behind these boarding schools and similar institutions. Multiple generations of his family were taken from their parents as children and sent to St. Mary’s Boarding School. He was lucky enough to meet Sister Eileen by chance through a webinar in 2020. This allowed him to tell his story to someone with a strong connection to this history.

Greengrass described his own connection to intergenerational trauma, saying that many descendants of boarding schools considered themselves to be survivors of genocide and systemic abuse. Greengrass tells of his grandfather who “had a hard time helping me with my homework due to his trauma.” Members of these schools would also have their hair cut off upon arrival. Hair, in many Native cultures, is seen as an extension of the self, and forcibly cutting it off, according to Greengrass, constituted an act of cultural erasure.

The assimilation of Native peoples was problematic for other reasons as well. Native Americans would receive no financial assistance if they did not send their children to boarding schools. The land that they occupied was often undesirable, located on either swampland or unfertile soil. They were even stripped from their parents as babies and sent to boarding school because, as Greengrass pointed out, the perception was that Native people “needed to be taught how to be civilized.”

The Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration have made efforts to listen to stories and cultivate relationships with indigenous peoples. Viterbo has plans to offer further educational opportunities about this history during Sister Thea Bowman Week.

When asked how faculty and students can help the healing process, Henry Greengrass advises members of the community to “Learn the history.”